24 Feb The Iceland plane wreck – a selfie story

This is a story of an air crash, wild beauty, film photography and selfies. It’s my recollection of a visit to the famous Iceland plane wreck site at Sólheimasandur – and of my view on the popularity of ‘abandoned’ places and the ubiquity of the selfie.

The story behind the Iceland plane wreck might already be roughly familiar to you. In November 1973 a small US Navy DC-3 transport aircraft ran out of fuel over southern Iceland, and ditched on the pristine black sand beach at Sólheimasandur. The wreck is still there – a weather-worn, graffiti-clad monument to Iceland’s inhospitable terrain.

I visited the Iceland plane wreck in 2016 during a two-week solo tour of the country via the ring road. It was my first ‘proper’ photography expedition; I’d been seduced by countless blog posts and travel stories pitching Iceland as a pristine wilderness: a place where I might find limitless solitude amid the glaciers and snow. For much of my trip, that’s precisely what I found – but not always. And the DC-3 wreck rings in my memory as an example of what can be a dispiriting experience at the hands of people who wield selfie sticks like rapiers.

The DC-3 crash site is a scene of Ozymandian barrenness. The remains of the US Navy aircraft glint on a lonely expanse of coal-black sand, Sólheimasandur, stretching far away towards bleak mountains peeking above an otherwise featureless horizon. When I visited, half-thawed snow accentuated the sand with mottled white patches of ice and slush. All was still and quiet – just the occasional faint clink of the fuselage warming up in the weak midday sun.

Quiet, that is, between the clucks and screeches of the dozen or so other tourists who’d made the long journey out to see the famous Iceland plane wreck. Apparently pulled to and fro by their selfie sticks, everyone clambered noisily across the aircraft’s bare skin, striving for the next perfect Insta pose. No-one seemed interested in the wild beauty of the landscape or the gentle decay of the old aircraft.

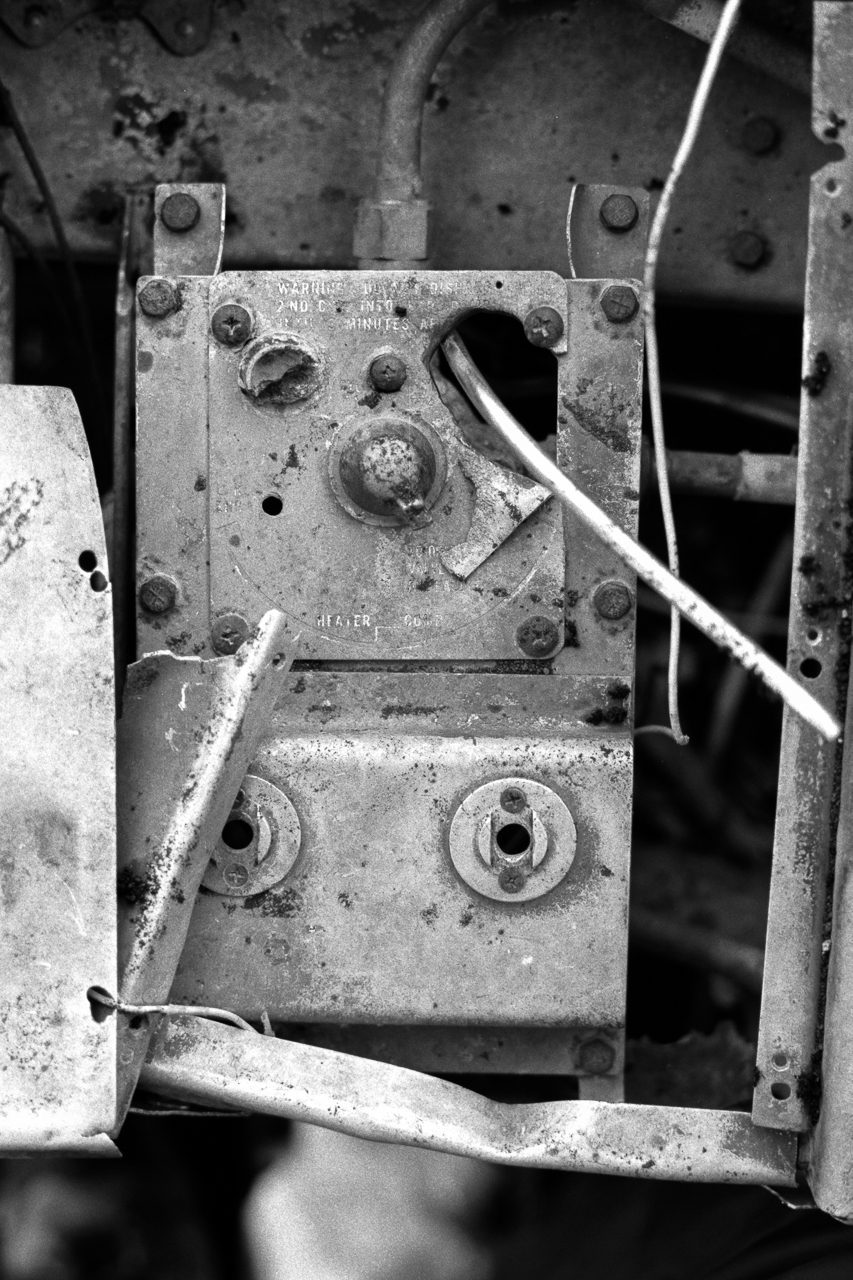

I waited for about an hour until the selfie crowd had left. Shooting on film, I made a series of pictures of the crashed DC-3 in its brilliant solitude: its gutted shell, its ragged wires and its old dials. Through the cockpit window I caught sight of two tourists skipping across the black sand; they paused and, faintly, I saw one of them retrieve a selfie stick. I finished my roll of film and was just leaving the aircraft as the two women approached, paused, posed and captured their selfies.

There’s something about the place-as-Facebook-post mentality that just doesn’t work for me. Those disposable moments – click, post, forget – surely transform the joy of discovering and marvelling at a new place into the brief thrill of ticking a checklist of must-have selfies. My landscape self-portraits, I freely admit, play into this – but I think the mentality behind them is entirely different. It’s to do with whose or what’s story is being told.

To my mind, my pictures are a comment on the landscape and of my place within it as a hiker and photographer. My pictures record journeys, and my awe at what I find along the way. They are, I think, landscapes first and foremost. At best, I might try to insert myself into the scene as foreground interest – a compositional tool. And I’m conscious that in doing so, I’m still making the viewer recognise and examine my own presence in the place. (I’m reminded of a line by the art educator Lawrence Gowing, on the subject of the self-portraitist: “Naturally he is not without vanity, without a little conceit few men could bear their mirrors of their lives. Moreover, the painter’s opinion of himself is a part of his equipment.”)

Vanity aside, the dominant character in my pictures is the landscape itself – from Japanese valleys to the Cheviots to Ardnamurchan. In selfies the dominant character is inescapably the person wielding the stick. They’re held front-and-centre: the first, perhaps the only thing that they really want the viewer to see is the subject, perfectly posed. Selfies don’t tell us much, if anything, about what scenery or object is behind the subject, or of why she is there. The place is a prop – an accessory to the subject’s need for approval.

Susan Sontag wrote about this in her essay In Plato’s Cave:

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it – by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs … Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter.

True enough – although the rise of the selfie now puts the tourist between the camera and the scene, recasting the viewer as the camera’s all-seeing eye. They compel us to ignore what’s beautiful and to focus on what’s incidental – not on the scene, but on the moment. It’s this transience that makes it entirely horrible to watch people queuing with selfie-sticks in galleries, ready to have their perfect moment recorded with some famous painting or sculpture. From the moment the shutter clicks the art becomes a disposable bauble, no longer there to be admired. I’ve seen this at work in the Uffizi, MoMA, the Guggenheim Bilbao, the British Museum, the Hakone Shrine…

Wherever you find beauty, these days you find selfies. And so we return to the Iceland plane wreck. Even in the depths of an Icelandic winter people seem determined to exercise their need to be seen in wild places. In doing so, my worry is that they fatally undermine the very quality that makes those places desirable: their solitude, silence and grandeur. I also worry about my own role in changing the character of these places.

As a photographer I think I have a duty to preserve what’s wonderful about the scenes I capture, but I know that every time I publish a picture or write a feature, I risk driving more people to visit, steadily turning those wild places into selfie scenes. (I’m also acutely aware of how this effect has forced me to employ the lie that lurks behind my pictures of that Iceland plane crash site: I captured it as I preferred to remember it, lonely and isolated; but the truth is, people are attracted to it like ants to a dropped ice cream cone.)

Ultimately my pictures are there to tell stories about travel – that’s certainly my intention with my photographs of the Iceland plane wreck. At the very least, I hope that by concentrating on the place itself, and not on my own vanity, I did something positive to honour the majesty of Iceland’s landscape, the lonely wreck and the solitude I can still find on the road – if I try hard enough.

No Comments